So Close To What, Exactly?

Tate McRae’s third album feels like a question she’s still figuring out.

Note: I began writing this piece 2 months ago, when So Close To What first released. I didn’t feel like I was able to fully articulate my thoughts, so I scrapped it. However, in retrospect, they are interesting, especially considering the current discussion surrounding Tate Mcrae.

I don’t know Tate McRae personally—but I grew up around her. We're the same age, from Calgary, and ran in adjacent circles as competitive dancers. We even had the same dance teacher at one point. She’s someone I’ve known of since childhood, and I’ve followed her career the way you might with an old classmate you never really spoke to—out of curiosity, maybe even a little pride.

In the North American dance world, dominated by powerhouse U.S. studios, seeing a fellow Calgarian rise to fame at The Dance Awards and Youth America Grand Prix felt surreal. She became the first Canadian finalist on So You Think You Can Dance, and then somehow, also a pop star. I remember when she was just a girl posting rough, emotional songs from her bedroom—tiny keyboard, echoey acoustics, all heart.

Though her music isn’t my typical taste, I’ve always been tuned in. I didn’t connect much with her debut; her voice felt too sharp and metallic for ballads, and the introspective persona didn’t match the fiery stage presence I knew her for.

But with Think Later, she started to find her footing. Singles like “Greedy” and “Exes” stood out. They were punchy, danceable, and aligned with her strengths: rhythm, attitude, presence. In a Gen Z pop scene dominated by melancholic introspection and Billie Eilish comparisons, Tate finally sounded like herself. Even she seems to agree, on “Cut My Hair”, she admits, “sad girl bit got a little boring.”

I was surprised when Tate McRae announced her third album, So Close To What. Think Later had just come out less than a year ago, and she was still actively promoting it on tour. Still, I was intrigued. The rollout included singles like “It’s Ok, I’m Ok,” “2 Hands,” and “Sports Car”—the last of which stood out the most. With whispery vocals layered over a sultry, intoxicating beat, the dirty-pop track feels bold, seductive, and dangerous that felt like an evolution from her previous hits.

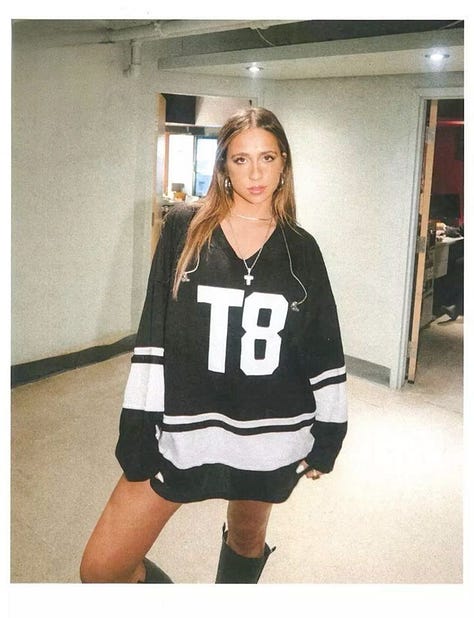

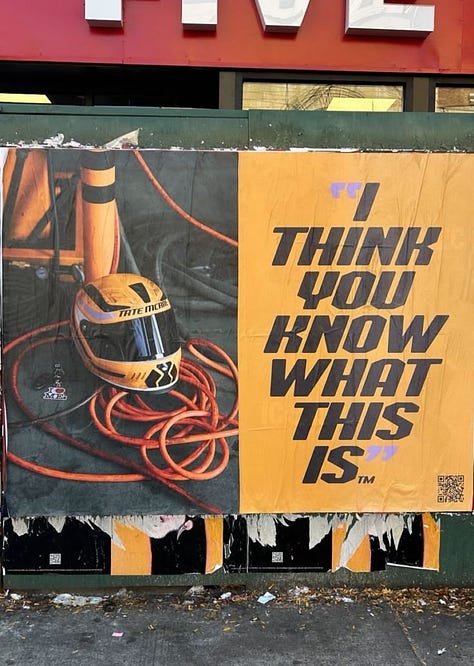

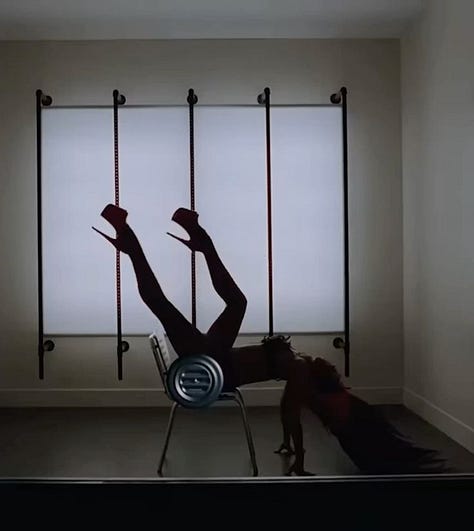

While Think Later leaned into a sporty-chic aesthetic—bedazzled hockey jerseys, matching Nike sets, cool-girl confidence—So Close To What trades jerseys for racing jackets. The theme is acceleration: ambition, desire, motion. According to Tate, the title represents “the journey of growing up when the road ahead feels infinite”—always chasing, never arriving. One accolade leads to another, but satisfaction never lasts. It’s a promising concept, especially for someone like Tate: an artist who's been in the public eye since she was a teenager but is only now breaking into mainstream recognition. She’s 21. Her career—and life—is just beginning.

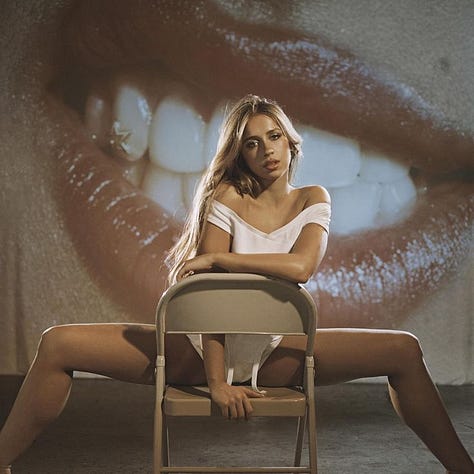

The album’s most striking moment comes on “Purple Lace Bra,” where Tate pauses to question her own image. In recent years, her style has become more overtly sexual—micro-shorts, low-cut dresses, sultry vocals and suggestive choreography. It’s her right, of course, to explore and own her sexuality. But it’s hard not to notice how suddenly it began—right after she turned 18 while backed by a major label. And Tate notices it too. “Did my purple lace bra catch your attention?” she asks, acknowledging the way her appearance is tied to the public's gaze. It’s a rare moment of self-awareness.

And yet, the reflection doesn't seem to lead anywhere. The rest of the album continues in the same overtly sexual tone—not in a nuanced or exploratory way, but in a polished, performative one. On one hand, maybe that’s the point: “You only listen when I’m undressed.” On the other hand, it feels like an opportunity for depth was left unexplored.

The same can be said of the album’s overarching concept. So Close To What is framed as a meditation on restlessness and ambition, but most of the tracks are about relationships: lust, love, betrayal, heartbreak. That’s not inherently a problem—there’s nothing wrong with writing about love—but the album’s branding feels disconnected from its content. I went in expecting a thematic arc and came out feeling misled.

There is space for her to bridge these ideas. Tate is currently dating another artist, The Kid Laroi, and she’s had a public breakup in the past. What does it mean to seek intimacy as a rising star? To navigate love in the spotlight while also chasing personal success? These are questions that could have deepened the narrative—ones only she can attempt to answer. But we don’t hear them.

One track, “Revolving Door,” comes close. In the bridge, Tate confesses: “Supposed to be on stage, but fuck it, I need a minute... / I'm supposed to be an adult, but fuck it, I need a minute.” It’s a striking moment of honesty—the kind that lingers. The exhaustion of constantly performing, both as an artist and as a young adult, is palpable. Judging by the wave of TikToks quoting these lines, it clearly resonated. And yet, the song doesn’t dwell there. The lyric hints at something larger—a deeper anxiety about adulthood, ambition, and identity—but it slips by, unexplored. These glimpses of something more complex flicker throughout the album, but they’re never fully unpacked. The restlessness she sings about never crystallizes into a narrative—we’re left grasping at threads that could have been stitched into something cohesive.

It’s not that Tate McRae is incapable of executing a concept. In fact, So Close To What proves the opposite. The recurring imagery of cars and racing—found in lyrics, music videos, stage outfits, even the tracks “Greenlight”—forms a consistent motif. She knows how to commit to a visual and thematic throughline when she wants to. Which is why the album’s core theme feels underdeveloped by comparison. The pieces are there: she is moving fast, chasing something, not sure where it’ll lead. But the metaphor never gets the weight it deserves. It’s aesthetic rather than psychological. Which, again, is fine. It just feels like a missed opportunity.

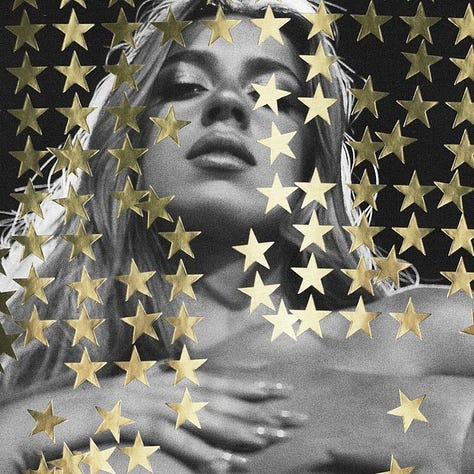

As Tate’s profile rises, comparisons to Britney Spears have become louder. Some are fair: they’re both dance-focused pop stars with instantly recognizable voices. And Tate clearly plays into it—her VMAs red carpet look paid homage to Britney. There are also nods to Christina Aguilera in the “Exes” music video, Pussycat Dolls energy in “Sports Car,” and Timbaland-style production throughout the album.

But when there are so many references, the line between tribute and identity crisis starts to blur. Tate McRae, as a pop persona, begins to feel more like a collage than a character. Of course, everything today is referential. In 2025, every chord progression and aesthetic has been recycled. Influence is inevitable. My own writing style is an amalgamation of the authors I love, the poets who moved me, the teachers who shaped my voice.

The same goes for Tate’s peers. Olivia Rodrigo pulls from the diaristic songwriting of Alanis Morissette and Taylor Swift and the alternative rock sensibilities of The Breeders amongst others—but her voice is unmistakably her own. Her songs read like the archives of a coming-of-age. Sabrina Carpenter borrows from the ‘50s pin-up playbook, while also mixing The Nanny with Madonna and Brigitte Bardot, but we still know who she is: cheeky, flirtatious, theatrical. She’s a pint-sized powerhouse whose lyrics are packed with innuendo and pastel charm.

Even Britney Spears herself was heavily inspired by Madonna, Janet Jackson, and Whitney Houston, for their presence, performance, and sheer pop power. But she didn’t just emulate them; she created something entirely her own. Not just an identity, but a pop iconography. Tate isn’t the first to draw the Britney comparison, and she won’t be the last.

But, who is Tate? Tate is sporty, yet sexy. Romantic, yet cold-hearted. She is a trained dancer with raw emotionality, but she’s also a label-backed product pushing hits and viral choreography. She’s the heartbroken girl next door and the pop vixen luring you in with a smirk. None of these identities are inherently contradictory—but the album doesn’t synthesize them into something cohesive in its arc. Instead, it cycles through personas without ever asking what they add up to.

I didn’t expect answers. But I was hoping for a question.

So Close To What isn’t a bad album—it’s catchy, polished, and will likely produce a few hits. But it lacks a distinct point of view. For all its talk of restlessness, speed, and ambition, the project feels like it’s still chasing something… undefined. We hear motion, but we don’t feel momentum. Maybe that’s what she meant all along. That she’s not there yet. That she’s so close—to what, exactly, she doesn’t know.

Update (April 2025): Since writing this review, Tate McRae has come under fire for her upcoming collaboration with Morgan Wallen, who has a well-documented history of racist behavior and controversy. For many fans—especially those who are queer, BIPOC, or both—the move feels like a betrayal. It’s hard not to see this choice as part of a larger pattern: Tate’s career continues to chase success at the cost of identity. Without a clear artistic center, she’s now risking the goodwill of the fanbase that helped bring her mainstream. And for what? Maybe that’s the answer to So Close To What—but it’s a disappointing one.