The tiny box TV cast long shadows across the living room as I sat curled on the couch, half watching the screen, half watching my mother make dinner. I was small—smaller than the couch, smaller than the world around me—and this movie felt impossibly large. Its words buzzed like warm static in my ears as I struggled to grasp the intricacies of the English language. I didn’t understand a word. But somehow, I understood the language of film.

I didn’t know what stop-motion was the first time I watched Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. I just knew it felt different. Warmer, somehow. A little odd, a little off-kilter, but alive in a way I couldn’t quite name. The clay figures moved with tiny, deliberate stutters, like the world they lived in was pausing to breathe between each frame.

And I loved it.

While other kids grew up on Disney princesses and high-speed animation, I fell for the wobbly, hand-crafted magic of stop-motion. Even now, when people call it creepy or uncanny, I just smile. To me, it was never eerie—it was intimate. Tangible. You could feel the fingerprints on every frame. It didn’t try to hide the strings—it showed them proudly. And somehow, that made the magic more real.

At six, old enough to be trusted with my mom’s phone, I started making stop-motion films of my own. I gathered my stuffed animals and carefully posed them in slightly different positions, snapping photo after photo, praying the illusion would come to life. I was small and impatient, so the films were never more than a minute or two—it took hours just to get that far.

I asked my dad to download a video editing app. I scribbled out ideas in a notebook, drew scene layouts with pencil crayons. I didn’t know the words screenwriting, storyboarding, producing—but that’s exactly what I was doing.

A teddy bear riding a unicorn. Two stuffed dogs dueling in a Fruit Loop-fueled rivalry. My Strawberry Shortcake plush marrying a dolphin while every Beanie Baby I owned sat in attendance. I layered in royalty-free music and unintelligible voiceovers which were more crunchy breathing into the microphone than dialogue. The results were clunky, choppy, chaotic. But I was hooked.

That spark never left me.

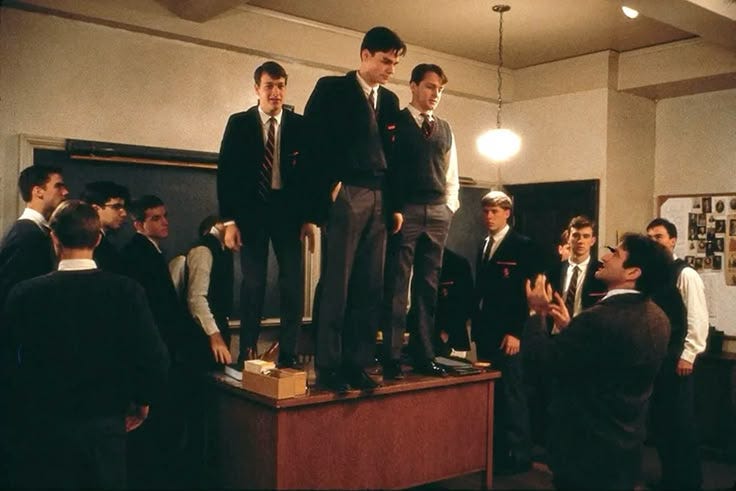

By the time I turned thirteen, I was studying film with the precision of a scientist and the wonder of an artist. I dissected movies like specimens—frame by frame, cut by cut—analyzing every decision a director made. I learned how a simple change in lighting could shift an entire mood, how a camera angle could change the way you felt about a character. It felt like being in a lab, uncovering the mechanics behind the magic.

But it was never just about the technique.

Film was also art—pure, aching, messy art. A way to tell stories that lived between the lines. I fell in love with the emotional undercurrents, the pauses that said more than words ever could, the brushstrokes of color and sound and silence. I observed how stories unfolded on-screen not just with logic, but with feeling. Film wasn’t just something I watched or made. It was something I felt in my bones.

I learned the language of the lens: wide shots that breathed, close-ups that ached, and cuts that could slice through time. Cinematography wasn’t just about crafting beauty—it was about guiding the eye, shaping emotion, and telling truths that couldn’t be spoken. I became obsessed with framing, composition, light. I’d pause a movie just to admire how the shadows fell on a wall, how a character was positioned against a window, how a tracking shot pulled you through a moment like a current.

And at the heart of it all—storytelling. I loved how films could be both deeply personal and universally understood. How two strangers on screen could hold up a mirror to your own life. I adored the details—the blue curtains, the warm lighting, the shadow on only half a character’s face. Every choice intentional. Every moment layered. Every element, human.

I watch new films to be transported and rewatch old ones to rediscover. To find new corners in familiar rooms. New emotions in lines I’ve memorized. I watch films to understand others, and sometimes, to understand myself.

Somewhere along the way, that love grew into a quiet dream. There was a moment, in that hazy stretch between youth and adulthood, when I almost pursued it for real. Cinematography. Directing. A life spent behind the lens, crafting the stories the way I’d always felt them.

If I had just a bit more courage, maybe I would have. But I chose a safer path instead. A steadier career. One with “stability” and “structure”.

Still, I haven’t let that part of me go. These days, the closest I get is filming and editing TikToks. It sounds silly, but it scratches the same itch. I still spend too long timing transitions to music, cutting clips for rhythm, thinking about natural light. Even in a 15-second video, I find the same joy—the puzzle of pacing, the beauty in a well-framed shot. The need to tell a story, however small.

I didn’t become a filmmaker. But I still see the world like one.

There’s a quiet comfort in knowing that. That no matter how far you go from your childhood dreams, some parts of them stay with you—forever part of the way you see, feel, and move through the world.